Dear friend

Go to the computer version of the site to view the full page animation

Periods of Greek sculpture

They were graceful and aristocratically prim. The statues were painted: hair, eyes and lips — red, clothes were decorated with a bright border and patterns of blue, red and green colors. A distinctive feature of archaic statues is the proportionality with the human body, and the presence of a natural smile. These features brought the statues closer to people, turning them from strict idols into objects of art. This transition also embodies changes in ancient Greek philosophy – a person becomes the center of the universe, his life, actions and problems are brought to the fore.

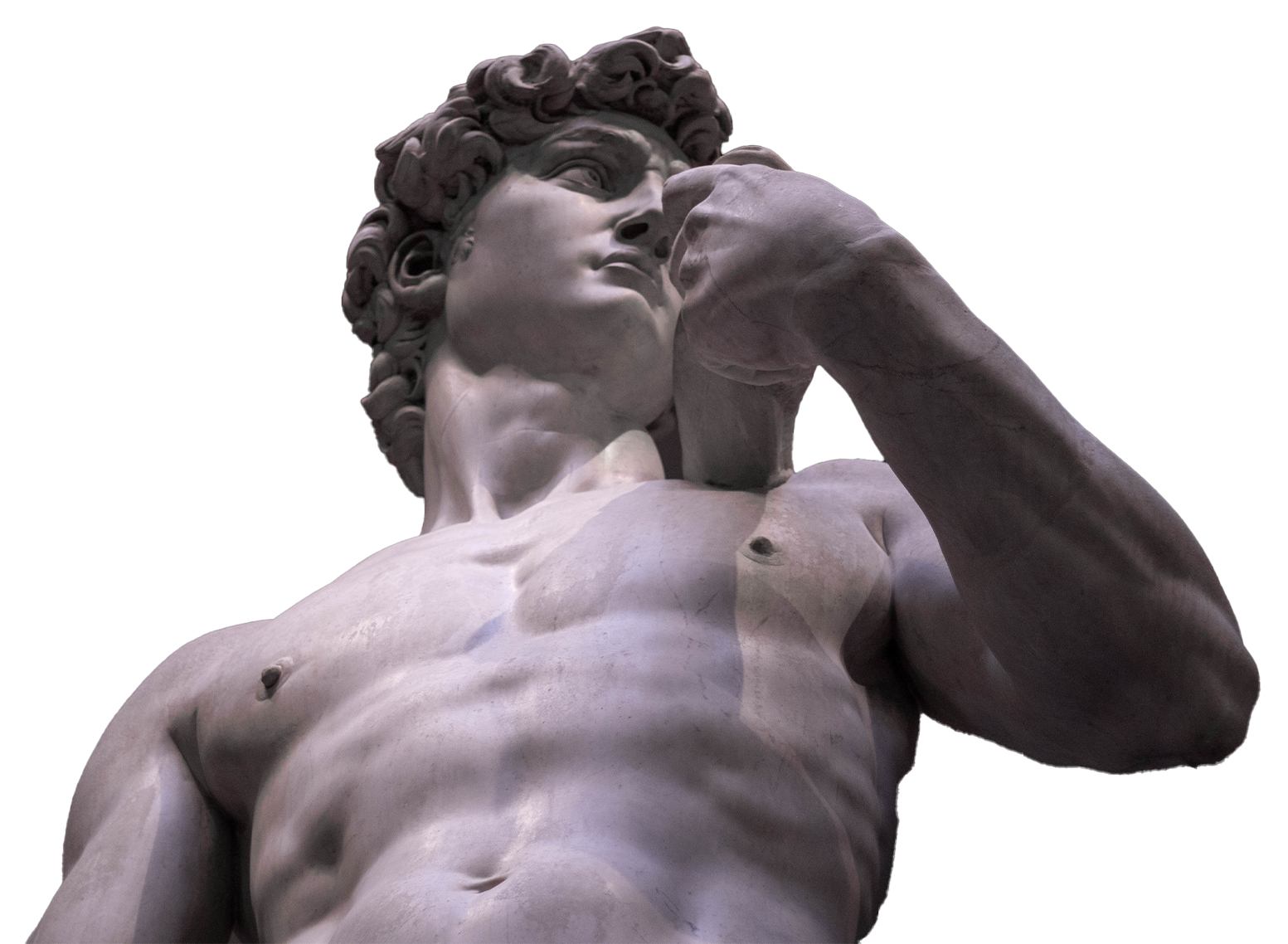

In the classical period, sculptors began to emphasize the harmonious combination of the physical and spiritual in a person. When creating sculptures, schematism and static disappeared. As before, the main images that inspired the artists are the gods, as well as the heroes of ancient Greece.

The classical period is divided into three parts:

Most of the most famous Greek sculptures belong to this era – "Charioteer", "Discobolus", "Diadumen", "Dorifor", and others.

In the bronze, marble and clay sculptures of the classics, the most truthful and natural transmission of human movement, facial expressions and anatomical structure is noted. At the same time, people are depicted in an idealized form, because the main principle of the Greek sculptors was the worship of beauty.

In the bronze, marble and clay sculptures of the classics, the most truthful and natural transmission of human movement, facial expressions and anatomical structure is noted. At the same time, people are depicted in an idealized form, because the main principle of the Greek sculptors was the worship of beauty.

The main difference in appearance between archaic Greek sculpture and classical style is in the poses. As a rule, most types of archaic statues were built from four strictly frontal or profile elevations, and although usually one leg was pushed forward and the other was pulled back, the left and right halves of the body were strictly symmetrical.

Classical statues still generally have a quadrangular shape, but the balance of the standing figure is shifted so that the axis of the body becomes a long double curve, and to soften the frontal, the head regularly turns to the side.

Classical statues still generally have a quadrangular shape, but the balance of the standing figure is shifted so that the axis of the body becomes a long double curve, and to soften the frontal, the head regularly turns to the side.

In reliefs and perimental sculpture, the archaic formula always allowed free movement, but each part of the figure was usually shown completely frontal or in profile. The classic style encourages sideways glances and even body turns.

This revolution in artistic anatomy, which probably began among painters, reached different directions of sculpture at different times. In low relief, it appeared with all the riot of novelty until about 500 BC, and in high relief – a little later. For a standing male statue, a relaxed pose first appears in the 480s BC, for a standing female statue, probably not earlier than the 470s BC. In order to maintain a comfortable boundary of 480, we can call the early examples of the new style transitional, but in fact they are already early classical.

This revolution in artistic anatomy, which probably began among painters, reached different directions of sculpture at different times. In low relief, it appeared with all the riot of novelty until about 500 BC, and in high relief – a little later. For a standing male statue, a relaxed pose first appears in the 480s BC, for a standing female statue, probably not earlier than the 470s BC. In order to maintain a comfortable boundary of 480, we can call the early examples of the new style transitional, but in fact they are already early classical.

Miron's creativity can be attributed to one of two trends that have developed in the art of classics. One of them, presented by the masters of Ionia and Attica, sought to reveal the beauty of movement, while the second, developed in the Peloponnese by the Argos-Sicyon school, created images of harmony based on the external immobility of the body, filled with the inner breath of life, hidden movement. To some extent, the great Phidias managed to combine both trends.

A contemporary of Phidias, the master of the second direction was Polycletus. His work falls on 460-420 BC.

A contemporary of Phidias, the master of the second direction was Polycletus. His work falls on 460-420 BC.

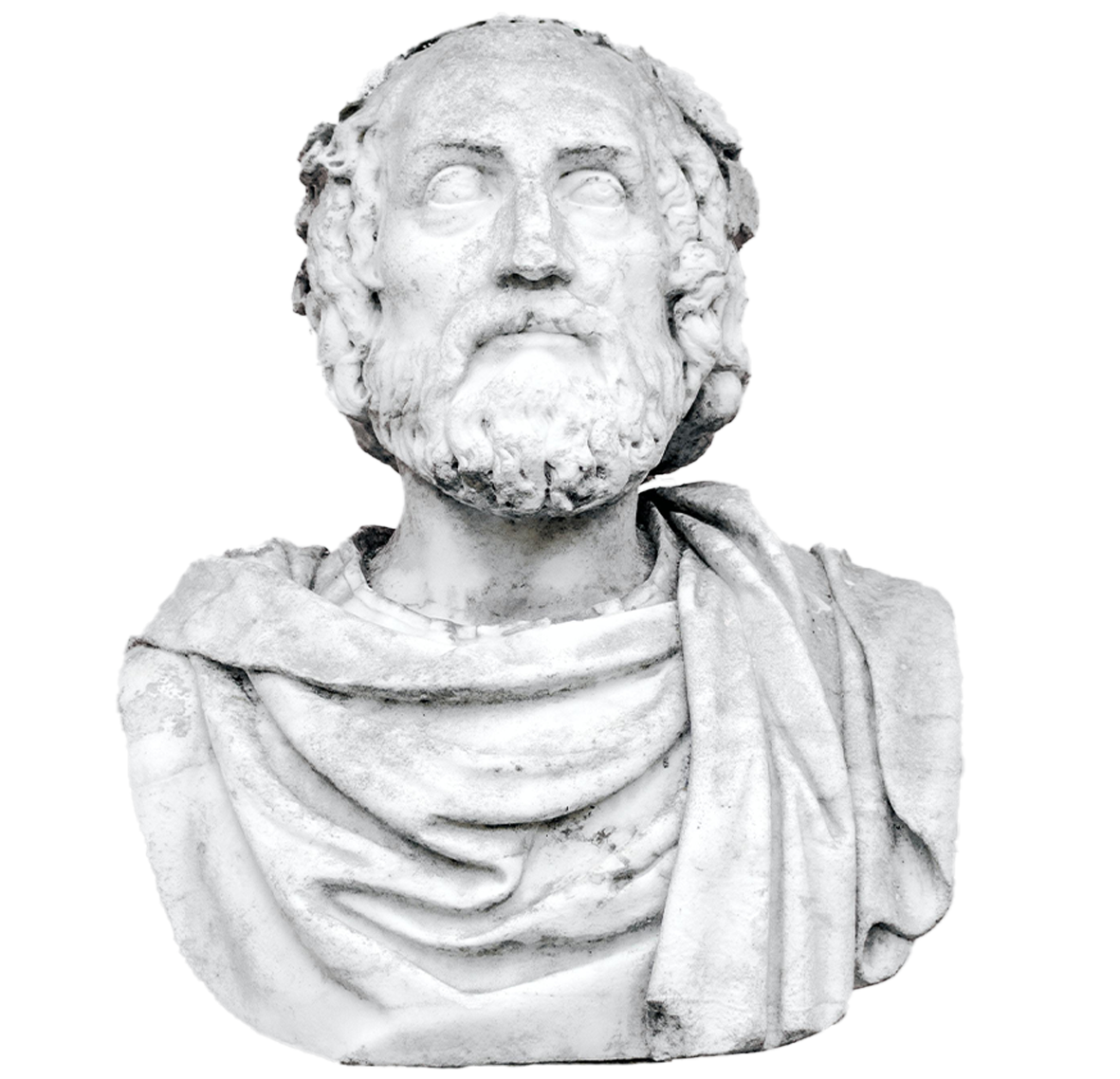

All the master's creativity was aimed at expressing the order, order and measure inherent in the universe and in man himself. Polycletus created the image of a heroically beautiful man, which, in fact, was the central theme of all Greek art, almost the only subject of which was a man or an anthropomorphic deity. According to the available written evidence, the sculptor used the phalanx of the thumb as a scale unit, the doubled length of which was equal to the thumb itself, and he, in turn, twice fit into the length of the hand.

However, Polycletus was not characterized by rigid, mechanical adherence to this scheme. Rather, he meant the canon as a general principle of deciphering the structure of the human body.

However, Polycletus was not characterized by rigid, mechanical adherence to this scheme. Rather, he meant the canon as a general principle of deciphering the structure of the human body.

In the IV century BC, Greek sculpture, without losing its perfection, took on a different character than before: new concepts and aspirations joined the great ideas and sublime feelings that gave rise to so many wonderful works in the age of Pericles; plastic creations became more passionate, imbued with drama, more sensual beauty manifested in them.

The material of the sculpture has also changed: ivory and gold were replaced by marble; metal and other ornaments were used less.

The material of the sculpture has also changed: ivory and gold were replaced by marble; metal and other ornaments were used less.

One of the representatives of the new direction was Scopas, the head of the Novoattic school. He sought to express violent passions and achieved this goal with a force that was not previously inherent in any sculptor. Scopas owned, among other things, the originals of the sculptures of Apollo Kifared, the seated Ares of Villa Ludovisi and, possibly, Niobides dying around his mother. He also created part of the reliefs of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus. Another great master of the same school, Praxiteles, liked, like Scopas, to depict deep feelings and movements caused by passion, but he succeeded best of all perfectly-beautiful youthful and half-childish figures with a hint of barely awakened or still hidden passion.

Unfortunately, very few sculptures created by Greek authors have survived to our time.

For the most part, these are later copies of Roman sculptors, created according to textual and graphic descriptions from the literature of that time.

Studying the preserved works of art, it is possible to track not only the stages of the sculptors' comprehension of this difficult skill, but also to compare them with the evolution of culture, philosophy, ideas about the outside world.

For the most part, these are later copies of Roman sculptors, created according to textual and graphic descriptions from the literature of that time.

Studying the preserved works of art, it is possible to track not only the stages of the sculptors' comprehension of this difficult skill, but also to compare them with the evolution of culture, philosophy, ideas about the outside world.

Antique sculptures still have a strong influence on modern culture and architecture, once again proving that the ancient Greeks were many centuries ahead of their time.